Why Human Responsibility Is the Missing Design Constraint in Machine Vision Systems

Machine vision projects are planned with engineering precision. Cameras are selected for resolution and frame rate. Optics are tuned. Lighting is simulated. Compute budgets are calculated down to thermal limits. Software capabilities are evaluated against performance benchmarks.

Yet one critical element is still treated as an afterthought: the human responsibility that remains once the system is deployed.

Not training time.

Not staffing levels.

Responsibility.

As machine vision systems move from inspection tools to decision-making infrastructure, organisations are redistributing responsibility across people and machines, often without explicitly defining where accountability begins and ends.

From observation to intervention

Historically, humans used vision systems to observe. The system highlighted features or defects, and people decided what to do next. Today, many systems are designed to act first, escalating only when thresholds are crossed or confidence drops.

This shifts the human role dramatically.

Operators are no longer primarily inspectors. They are validators, exception handlers, and risk owners. They are asked to approve outcomes they did not personally observe, explain decisions they did not directly make, and intervene quickly when something unusual occurs.

Crucially, this role change often happens without the job itself being redesigned.

Responsibility without proportional insight

Here is the core tension emerging in modern deployments: humans remain accountable for outcomes, but their visibility into how those outcomes are produced is shrinking.

When a vision system flags an issue, the human is expected to respond. Yet in many cases, they are given limited insight into why the system reached that conclusion, how confident it is, or what assumptions underpin the decision.

The interface may present a result, but not the reasoning. It may show a detection, but not the uncertainty. It may allow an override, but not a meaningful interrogation of alternatives.

This is not a failure of accuracy. It is a failure of decision support.

The consequence is rarely outright mistrust. More often, it is hesitation. And in production environments, hesitation erodes the very efficiency automation was meant to deliver.

The invisible cost layer

This human layer is rarely budgeted because it does not fit neatly into traditional procurement categories. It sits across disciplines, part interface design, part organisational workflow, part risk management.

As a result, it is frequently postponed until late in the project, or treated as something that can be “fixed with training” after deployment.

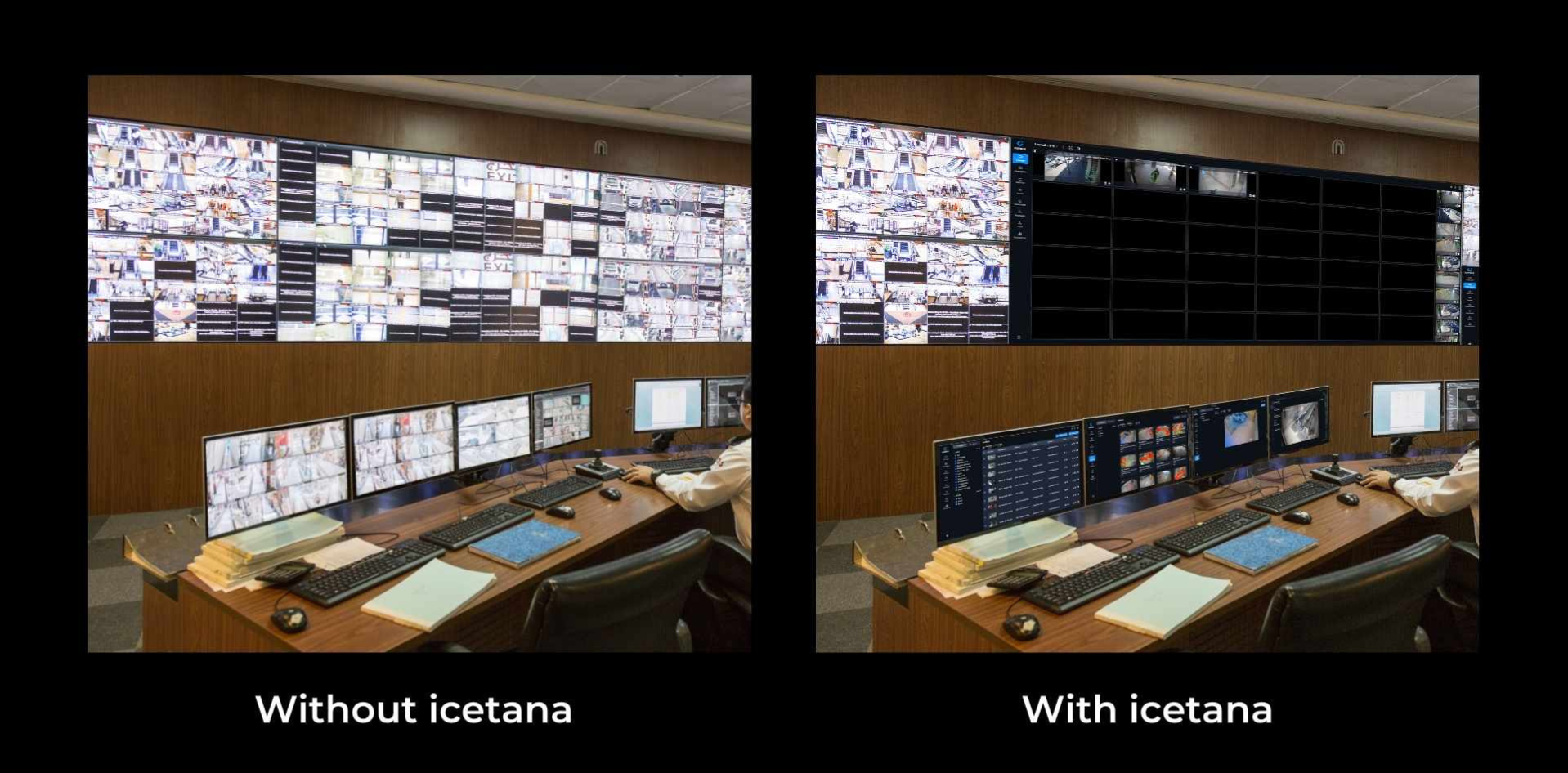

In practice, this omission has tangible costs. Systems that look successful on paper deliver limited operational impact. Alerts are acknowledged but not acted upon. Operators quietly add manual checks “just in case”. Vision becomes advisory rather than authoritative.

None of this shows up in specification documents. All of it shows up in long-term ROI.

Why this matters more in 2026

In 2026, machine vision is no longer emerging technology. It is infrastructure.

And infrastructure behaves differently from tools. It shapes workflows, redistributes responsibility, and defines how decisions are made at scale.

At this stage, success is no longer determined by whether a system can see accurately, but by whether people understand how to work with what it sees. That understanding cannot be bolted on later. It has to be embedded deliberately into system design.

Designing for accountability, not supervision

The most effective vision systems are not those that demand constant human oversight, nor those that attempt to remove humans entirely.

They are systems that make accountability explicit.

This means designing interfaces that surface confidence and uncertainty, not just outcomes. It means creating escalation paths that align with real operational authority. It means giving operators the ability to ask meaningful questions of the system, not just accept or reject its output.

Above all, it means acknowledging that human judgment is not a weakness to be eliminated, but a capability to be supported.

A design constraint the industry can no longer ignore

The human factor is not a camera problem.

It is not an AI problem.

And it is not a training problem.

It is a design problem, one that sits at the intersection of technology, people, and responsibility.

As machine vision systems continue to take on higher-stakes roles, ignoring this layer will increasingly limit their effectiveness. Not because the technology cannot perform, but because we have not clearly defined how humans are meant to perform alongside it.

In 2026, budgeting for the human factor is no longer optional. It is the difference between systems that technically work and systems that actually deliver value.

Further reading: The more cameras we deploy, the less we actually see — Macnica ATD